El Niño is gaining steam in the Pacific Ocean and forecasters are now leaning towards it being a strong event, the first since the blockbuster El Niño of 1997-1998. That possibility is again raising the collective hopes of Californians that this winter may finally see some desperately needed precipitation to begin the slow climb out of a historic drought.

“In California, all eyes are on the Pacific given the ongoing historic drought,” Daniel Swain, an atmospheric science Ph.D. student at Stanford University, said in an email.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued its latest monthly El Niño forecast on Thursday, calling for a better than 90 percent chance that this event will stick around through the fall months, and an 85 percent chance it will last through the winter. Forecasters also took their first stab this year at projecting the intensity of the event, with the odds right now favoring a strong El Niño. There is, as always with such forecasts, the niggling possibility that it could remain a weak event or even fizzle out.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“We can’t rule out a ‘97-‘98-like event,” NOAA forecaster Michelle L’Heureux said, but nor can they say that it will definitely happen.

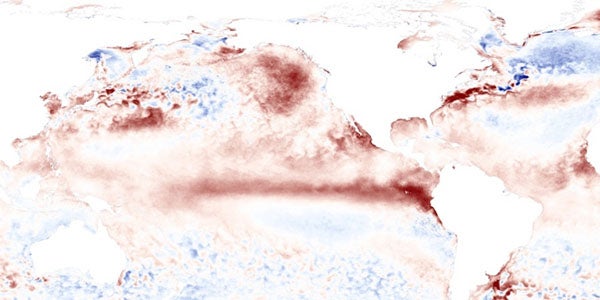

Sea surface temperatures anomalies across the Pacific Ocean from June 1 to June 7, 2015, when an El Niño event was in place. Credit: NOAA View

If the El Niño does become a strong event and stays that way through the winter, that means there’s a good chance California could finally see some healthy rains come winter, the traditional wet season there, which has come up dry in recent years. But after El Niño failed to flourish last year, hopes are seasoned with more than a few grains of salt.

“This year people have the perspective of last year’s failed prediction of El Niño to temper the enthusiasm of the predictions in play this year,” California state climatologist Michael Anderson said in an email.

Atmospheric domino effect

El Niño is a climate phenomenon that happens in the Pacific Ocean, but it causes an atmospheric cascade that can alter normal weather patterns across the globe.

An El Niño is primarily defined by the warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures it brings to the central and eastern tropical Pacific, but that’s not all there is to it. That excess ocean warmth bleeds into the atmosphere, which tends to shift storm activity from west to east in the same region.

That shift then creates a domino effect that alters other atmospheric patterns, for example causing stable, subsiding air to dominate over the main hurricane cradle of the Atlantic, tamping down on tropical cyclone activity there.

Some of the shifts caused by El Niño can alter rainfall patterns, bringing drought to places like Indonesia and Australia, but increased rains to parts of South America. And if the El Niño is a strong one, more often than not it tends to mean more winter rains in California.

Battle of the jet streams

The ramped up rains there happen because of the effect El Niño can have on the main jet streams, the ribbons of fast-moving air that guide storms from west to east.

Normally in winter, California depends on dips in the polar jet stream to send it the storms that bring the bulk of its yearly precipitation. But during an El Niño, the subtropical jet stream tends to get a boost, while the polar jet stream weakens, Swain explained in a recent post on his blog.

But the extent of the relative shifts in jet strength depends on how strong the El Niño is. If it is a weak event, it has less of an effect on the jet streams, which can result in two weak jets duking it out for influence and varying effects for California.

“If California’s lucky, we see moist storms originating from both regions, but if we’re unlucky, we can largely miss out on storm systems taking both trajectories,” Swain wrote.

But a strong El Niño can ramp up the subtropical jet enough that it wins out. This can mean a stream of strong storms that have a direct tap into tropical moisture sources — translation: lots of potential rain for California.

Of course, it’s not a 100 percent certainty. “There are exceptions, so even a stronger event is not a guarantee that they’ll be increased rainfall,” L’Heureux said.

These varying outcomes for California are one reason why so much attention is paid to the expected strength of El Niño events and why forecasters try to predict it even several months out, when such forecasts are very shaky.

Strong signs

Right now, all of the models that forecasters use, as well as observations of what’s currently happening in the tropical Pacific, are indicating that this El Niño is going to be a strong one come late fall and winter, when it usually peaks.

For one thing, the characteristic connections between the ocean and atmosphere that were so lacking throughout last year have finally clicked and are showing up consistently.

And there is quite a bit of pent up heat in the tropical Pacific, which has been building up since the El Niño first showed signs of emerging in spring 2014.

“It’s sitting there bottled up in the tropics, waiting to be released,” L’Heureux said, which also helps bolster the odds of a strong event.

What remains to be seen is if the models and observations continue to bear out that expectation as it gets closer and closer to winter. Forecast accuracy tends to improve progressively the nearer to that season it gets.

And if that El Niño does become a strong event, it needs to stay that way until winter for California to see any benefit.

“The key is really whether this event maintains its strength into the winter,” Swain said. “While the models do think that will likely happen, we still don't know for sure.”

More hurdles to clear

Even if the El Niño does become strong and stays that way through the winter, there’s another piece to California’s drought recovery puzzle that isn’t guaranteed. One reason it is in such a terrible drought is the lack of a healthy snowpack in recent winters. That snow is what helps ensure that reservoirs stay supplied throughout the dry spring and summer months, as the snow gradually melts and keeps them topped up.

This past winter saw the lowest snowpack in California’s recorded history—a measly 6 percent of normal at the traditional April 1 measurement. That dismal reading was a catalyst for the first statewide water restrictions ever mandated there.

The reason the snowpack was so meager was because temperatures were record warm throughout the season, meaning that even when rare storms came through, they dropped rain and not snow, even at higher elevations.

Past strong El Niño events, such as in 1982-1983 and 1997-1998, have seen robust snowpacks, Swain said, but they may not be the case with any event now or in the future. For one thing, the Pacific off the California coast is still very warm, which tends to keep temperatures over the state warm as well. For another, there’s global warming.

“California has experienced a significant temperature increase over the past several decades, which is a hallmark of global warming,” Swain said. “So it's hard to say whether what has been true historically about El Niño and Sierra snowpack will hold true for the present event.”

Even if all the various hurdles for this El Niño event are cleared—it becomes strong and stays that way through winter; it brings sustained rains; and it provides a healthy snowpack—California won’t be drought free come spring. The drought is one of truly historic proportions that was the result of year-after-year dryness. Because it took multiple years to dig such a deep hole, it’s going to take several to fill it back in.

“California would probably need to experience its wettest year on record (by a fairly wide margin) to erase ongoing deficits in a single year,” Swain wrote on his blog. “While it’s not physically impossible, that would be a very tall order, indeed.”

This article is reproduced with permission from Climate Central. The article was first published on June 10, 2015.