What Really Happened to Ben Chapman, the Racist Baseball Player in 42?

He told me he always wanted to be recognized as a great player. But his harassment of Jackie Robinson will now forever define his place in history—as is fair.

In 1979, having graduated the University of Alabama with no ambition more worthwhile than becoming a sportswriter, I had occasion to meet Ben Chapman—the "Alabama Flash," as we knew him—during a college baseball game at Rickwood Field in Birmingham.

"You ought to come over and interview me sometime," he said. "I'll tell ya some stories."

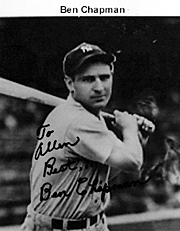

"I'll bet you could," I thought to myself. I knew Chapman only by reputation. He had been a pretty good ballplayer on the Ruth-Gehrig Yankees and then later with several other teams, but he was remembered for his savage heckling of Jackie Robinson in Robinson's first year in the major leagues, 1947, when Chapman was manager of the Philadelphia Phillies. Chapman was 71 and gray-haired when I met him, but he looked younger, and very fit—unlike most former big leaguers I've encountered over my career.

I took him up on his offer to talk, and we got together the following week. He was very gracious, always smiling. But when the talk turned to something he was uncomfortable with, the smile seemed to freeze and he bared his teeth. This happened about two minutes into our interview.

"Is it true," I wanted to know, "that you said those things to Jackie Robinson? You know, the names, the words, that everyone said you used?"

"Heck, yeah," Chapman said with a loud guffaw. "Sure I did. Everyone used those kind of words back then. Heck, we said the same things to Joe DiMaggio and Hank Greenberg."

I was puzzled. "You mean you called DiMaggio a ....?"

"We tried to rattle him by saying, 'Hey, Dago' or 'Hey, Wop.'"

What about Greenberg? "Oh, we called him 'Kike.' It was all part of the game back then. You said anything you had to say to get an edge. Believe me, being a southerner, I took a lot of abuse myself when I first played in New York. If you couldn't take it, it was a case of if you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen."

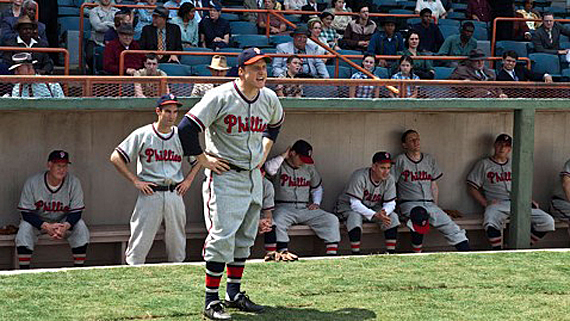

In one of the most intense scenes in the film 42, the story of Jackie Robinson that first season when he broke the color barrier, Chapman's abuse of Robinson is recreated with chilling effect. What hit me like a fastball to the side of the head, though, was the next scene where reporters grill Chapman (played by Alan Tudyk): The movie Chapman defends his behavior in almost exactly the same way the real Ben Chapman did to me.

It was then I realized that for more than three decades Chapman must have been telling reporters the same things he had told me.

Over the years, retired players and sportswriters I've talked to have confirmed that, yes, baseball banter was pretty harsh back then and ethnic slurs and insults were a big part of Depression-era and post-World War II baseball. They did say those things to DiMaggio and Greenberg, and, yes, a lot of northern players did harass southern boys mercilessly. (Sample: Ed Walsh, born and raised in Pennsylvania, loved to yell at. Georgia-born Ty Cobb, "Cobb, I hear you're from Royston, where men are men and sheep are nervous!")

But as Lester Rodney—"Press Box Red," who wrote about sports for the Communist paper The Daily Worker—once told me, "That Chapman, he was something special. He could taunt with a viciousness that would have made Ty Cobb blush." As Rodney pointed out, DiMaggio and Greenberg could give it right back, but Robinson wasn't allowed to: "Jackie had promised Branch Rickey that in his first season he wouldn't fight back."

What Chapman really wanted to talk about in our interview wasn't Jackie Robinson; it was why he (Chapman) had been slighted by the Hall of Fame and how the taint over his dismissal from the Phillies in 1948 (he had just one more stint in the majors, as a coach with Cincinnati in 1952) had unfairly kept him from being considered for Cooperstown.

I didn't buy his argument, but, as I said, Chapman had been a pretty good player. He survived 15 years in the majors with a batting average of .302, twice driving in more than 100 runs and six times scoring more than 100. He was quick to remind you that he had led the league in stolen bases in four seasons—which, when I checked the record book, I found out was true. But he neglected to tell me that he also led the league four seasons in being thrown out attempting to steal. He was a superb outfielder (though as a shortstop he made so many errors in his first season that the Yankees replaced him with another Alabamian, Joe Sewell). And Chapman had the distinction of being the first American League player to get a hit in the first All-Star game, 1933.

But the truth is that Chapman, his encounters with Robinson aside, wasn't quite Hall of Fame caliber. He hit for a pretty good average at a time when many players were hitting for high averages—batting .332 in his best year, 1936, while playing for the Washington Senators. When I mentioned this to Ben, he just shook his head and smiled.

Anyway, the interview, except for the subject of race baiting, was pleasant, and I came away with an autographed picture.

I saw him again six years later, by which time I was living in Brooklyn. I went home for an old-timers game at Rickwood Field. It was Rickwood's 75th anniversary, which still stands today as the country's oldest professional ballpark. Chapman managed a team of All-Stars; the other team was managed by Piper Davis, nine years younger but practically a contemporary of Chapman's. Piper never got the chance to play in the big leagues because of the color barrier. After Jackie Robinson opened the doors, Piper signed a contract with the Boston Red Sox but never got to play a game. Most of the players and managers I talked to over the years thought Piper could have been a Hall of Famer himself.

During the game, both men seemed to be having a good time. Afterwards, they laughed and slapped each other on the back. I was surprised, to say the least.

Several years later, while working on a book on Rickwood Field, I asked the former owner of the Birmingham Barons, Art Clarkson, about that night. "All I can say," he told me, "is that Ben really was a different man in his later years—he acknowledged the error of his old ways. I remember telling him that I was going out to a school in a black neighborhood to talk to kids about baseball, and he volunteered to go along. He talked to the kids and really seemed to enjoy it. To tell you the truth, I don't think he had had the opportunity to do something like that before. I think he discovered something in himself that he didn't know was there."

Well, as my mother used to say, just when you think you know someone. Chapman died in 1993, age 84. Because of the success of 42—its opening weekend was the highest of any baseball movie ever—the Ben Chapman portrayed in the movie will certainly define his image in baseball history. And that's fair. But it's just possible that near the end of his life Chapman did change—or as we say today, he evolved. At least some people who knew him in his later years thought he did, and I think it's fair, also, that in some tiny corner of baseball history that Ben Chapman is be remembered as well.